Last week, Lockheed Martin announced that it had a hypersonic replacement for the storied SR-71 Blackbird in the works. At this point, the most surprising element about it is that I haven't written about it yet. Bear with me--this post probably doesn't end how you think it will.

The story (linked above) was broken as an exclusive by Aviation Week. Lockheed has since posted its own news release on the subject, but that has really been the extent of the solid information out there. Much was rehashed over the weekend, so I'll do a "good parts" version here.

What is the SR-71's replacement? Why... it's the SR-72, of course. And it's not yet an official U.S. project; instead, Lockheed Martin (and some partners) have been working on their own to develop some of the technology to make a Mach 6 aircraft possible. The easy part: making it look awesome.

The hard part: propulsion. The materials needed for an airframe to survive hypersonic flight are well-known and tested. Manned aircraft like the X-15 have explored the flight regime. The Space Shuttle, of course, entered the atmosphere at near-orbital speeds, many times faster than that planned for the SR-72.

No, the problem is that traditional air-breathing engines generally only work well up to speeds of a Mach 2.2 or so--just more than twice the speed of sound. Beyond that, the air is moving too fast and is too hot to adequately compress inside the engine (compression and expansion being, essentially, the processes that give a jet its thrust).

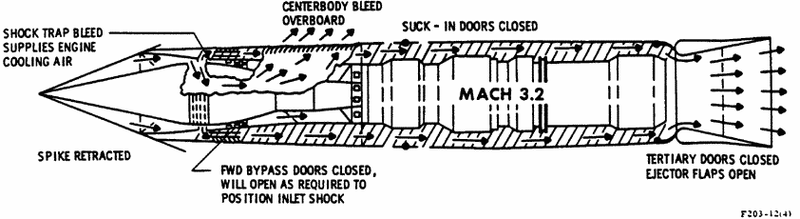

The SR-71 overcame that with clever engineering. Massive spikey things called, well, "spikes," were mounted in front of its J-58 engines and adjusted depending on how fast the aircraft was traveling.

The spikes created a shockwave that fed air into the engines at a manageable velocity. But wait, there's more! The air heats up dramatically as it is slowed down--or actually accelerated, as the spike hits stationary molecules--because all that kinetic energy has to go somewhere. The hot air is much harder to compress. And less compression means less thrust. But The good people of Skunk Works had a solution for that too.

You with me? Large amounts of heated air were simply routed around the engine's core. That left cooler air to run through the compressor. But it also allowed the remaining air to be "reheated" in the exhaust--what is commonly called an afterburner. The compressor then ran more efficiently AND the volume of air passing through the engine was high enough that simply spraying fuel into the exhaust generated most of the engine's thrust at its top speed.

So those are the SR-71's engines. In effect, they went from being turbojets to near-ramjets at Mach 3.2.

This is important, because ramjets are needed for hypersonic flight. The techniques used in the SR-71 simply won't stand up at Mach 6, or six times the speed of sound--among other things, the temperatures are too extreme and the materials in the engines would simply melt.

The solution is engines without any moving parts--the ramjet.

But this introduces another problem. Ramjets only work efficiently at speeds above Mach 4 or so... in other words, perhaps 500 mph faster than any jet-powered aircraft has flown. They don't work at all at a standstill. And that's a big problem if you want your aircraft to, you know, take off from a runway.

Lockheed Martin says it has solved this problem by putting both types of engines in the aircraft and tweaking both of them: the turbojet can go a little faster and the ramjet can get started a little slower.

The company won't say how, exactly, it has done this, but the engineers seem pretty confident:

And with that issue solved, somehow, a Mach 6 aircraft is suddenly quite feasible.

To me, the entire thing is fascinating. I always loved the SR-71, which looks awesome and is awesome, so the idea of a successor that is twice as fast is beyond intriguing. But you know what else is intriguing? The fact that Lockheed Martin went public with this. If speed really is the new stealth, as the company puts it, why would you want to tip your hand?

Clearly, it's a business decision. Projects like this don't get built without a customer. And the only buyer is, of course, the U.S. government... which has had its share of budget issues lately. So you go public with something you think only you can pull off; this perception creates demand.

Lockheed Martin is also a player in the competition to build the Air Force's Long Range Strike Bomber. Putting some information out there that implies you can do something the other guys can't isn't a bad way to "taint the jury" for a contract that will be worth many billions of dollars.

And finally, the company has created value for itself. Its stock price jumped nearly $2 at one point on Friday. Getting your name in the news will do that.

So in the end, what is the SR-72? In my mind, it is probably a chess move--using a technical achievement to accomplish a long-term goal for the company. But in my aviation dork heart, I hope it becomes the real deal... faster, higher and awesomer than even the Blackbird.

The story (linked above) was broken as an exclusive by Aviation Week. Lockheed has since posted its own news release on the subject, but that has really been the extent of the solid information out there. Much was rehashed over the weekend, so I'll do a "good parts" version here.

What is the SR-71's replacement? Why... it's the SR-72, of course. And it's not yet an official U.S. project; instead, Lockheed Martin (and some partners) have been working on their own to develop some of the technology to make a Mach 6 aircraft possible. The easy part: making it look awesome.

The hard part: propulsion. The materials needed for an airframe to survive hypersonic flight are well-known and tested. Manned aircraft like the X-15 have explored the flight regime. The Space Shuttle, of course, entered the atmosphere at near-orbital speeds, many times faster than that planned for the SR-72.

No, the problem is that traditional air-breathing engines generally only work well up to speeds of a Mach 2.2 or so--just more than twice the speed of sound. Beyond that, the air is moving too fast and is too hot to adequately compress inside the engine (compression and expansion being, essentially, the processes that give a jet its thrust).

The SR-71 overcame that with clever engineering. Massive spikey things called, well, "spikes," were mounted in front of its J-58 engines and adjusted depending on how fast the aircraft was traveling.

To go fast, you have to slow the air down.

The spikes created a shockwave that fed air into the engines at a manageable velocity. But wait, there's more! The air heats up dramatically as it is slowed down--or actually accelerated, as the spike hits stationary molecules--because all that kinetic energy has to go somewhere. The hot air is much harder to compress. And less compression means less thrust. But The good people of Skunk Works had a solution for that too.

Skip the compressor--who needs it?

You with me? Large amounts of heated air were simply routed around the engine's core. That left cooler air to run through the compressor. But it also allowed the remaining air to be "reheated" in the exhaust--what is commonly called an afterburner. The compressor then ran more efficiently AND the volume of air passing through the engine was high enough that simply spraying fuel into the exhaust generated most of the engine's thrust at its top speed.

So those are the SR-71's engines. In effect, they went from being turbojets to near-ramjets at Mach 3.2.

This is important, because ramjets are needed for hypersonic flight. The techniques used in the SR-71 simply won't stand up at Mach 6, or six times the speed of sound--among other things, the temperatures are too extreme and the materials in the engines would simply melt.

The solution is engines without any moving parts--the ramjet.

Cold air goes in, hot air comes out--it's that simple.

But this introduces another problem. Ramjets only work efficiently at speeds above Mach 4 or so... in other words, perhaps 500 mph faster than any jet-powered aircraft has flown. They don't work at all at a standstill. And that's a big problem if you want your aircraft to, you know, take off from a runway.

Lockheed Martin says it has solved this problem by putting both types of engines in the aircraft and tweaking both of them: the turbojet can go a little faster and the ramjet can get started a little slower.

Like this, but less vague.

The company won't say how, exactly, it has done this, but the engineers seem pretty confident:

“We have developed a way to work with an off-the-shelf fighter-class engine like the F100/F110,” notes Leland. The work, which includes modifying the ramjet to adapt to a lower takeover speed, is “the key enabler to make this airplane practical, and to making it both near-term and affordable,” he explains.

--snip--

Lockheed will not disclose its chosen method of bridging the thrust chasm. The company funded research and development, and “our approach is proprietary,” says Leland, adding that he cannot go into details. Several concepts are known, however, to be ripe for larger-scale testing, including various pre-cooler methods that mass-inject cooler flow into the compressor to boost performance. Other concepts that augment the engine power include the “hyperburner,” an augmentor that starts as an afterburner and transitions to a ramjet as Mach number increases. Aerojet, which acquired Rocketdyne earlier this year, has also floated the option of a rocket-augmented ejector ramjet as another means of providing seamless propulsion to Mach 6.

And with that issue solved, somehow, a Mach 6 aircraft is suddenly quite feasible.

To me, the entire thing is fascinating. I always loved the SR-71, which looks awesome and is awesome, so the idea of a successor that is twice as fast is beyond intriguing. But you know what else is intriguing? The fact that Lockheed Martin went public with this. If speed really is the new stealth, as the company puts it, why would you want to tip your hand?

Clearly, it's a business decision. Projects like this don't get built without a customer. And the only buyer is, of course, the U.S. government... which has had its share of budget issues lately. So you go public with something you think only you can pull off; this perception creates demand.

Lockheed Martin is also a player in the competition to build the Air Force's Long Range Strike Bomber. Putting some information out there that implies you can do something the other guys can't isn't a bad way to "taint the jury" for a contract that will be worth many billions of dollars.

And finally, the company has created value for itself. Its stock price jumped nearly $2 at one point on Friday. Getting your name in the news will do that.

So in the end, what is the SR-72? In my mind, it is probably a chess move--using a technical achievement to accomplish a long-term goal for the company. But in my aviation dork heart, I hope it becomes the real deal... faster, higher and awesomer than even the Blackbird.

No comments:

Post a Comment